DPD Causes

The information any one game needs to present is wide and varied. Thus the methods for presenting and acquiring the information is equally as varied.

The following list details some of the major mistakes that can result in DPD.

Disclaimer: The nature of this topic means that a lot of this (the examples in particular) comes from my subjective personal experience. Not everyone will get stuck at the same places in a video game and what might catch one player off-guard may be second nature to another.

1: Not Explaining All the Rules

It’s important when starting a game of any sort, that all of the players know all of the currently relevant rules. Can you wall-jump in a platformer? What moves can you block (or counter) in an action game? If a solution results in exclamations of, “I didn’t know I could do that!”, then you have a case of DPD.

In the jumping puzzler Starseed Pilgrim; your goal is to plant seeds to grow different shapes which you can then jump on to reach stars and doors. Seeds are built up as a really valuable resource, as you need to not only plant them in the level, but also in the post-level challenge, and in the overworld.

Planting is disabled in the game’s inverse world and you’re often left with untraversable gaps between you and the door to the post-level challenge. What the game doesn’t tell the player is they have a ‘bubble-jump’. Bubble-jumping creates a bubble around the player character so they can control a sideways or upwards float. However, this only works in the inverse world, while you are midair, with the ‘plant seed’ button, and spends a seed as currency. Worse than being unexplained, this rule goes counter to the expectations that form the foundation of the rest of the game.

2: Exceptions to the Rule

Sometimes a game rule is true 99% of the time. But in that case, the game has built up the expectation that the rule is true 100% of the time. And that 1% can be the most frustrating moment of DPD in the entire game.

In Shantae and the Pirates Curse, there are collectable ‘heart-squids’. These health-increasing little guys are scattered about the game and they are always clearly visible. You can’t always get to them right away, but that’s fine. It is less about where the squid is and more about how to access them.

Except for one in the Tan Line Island dungeon. This guy is completely hidden behind a destructible block in a dangerous corner.

Besides the ‘squids are visible’ rule, this also breaks the ‘destructible blocks are only obstacles’ rule. Hiding a squid here would have been perfectly fine if there was a precedent of blocks hiding treasure (gems or items) but that is not the case. Other blocks prevent you from getting treasure but are never holding the treasure themselves.

3: Overly Specific Solutions

As smart, tool-using primates; we as a species expect that pretty much anything is multipurpose. And yet, despite having this perfectly good lighter or a loaded gun or just a strong pair of hands, the adventure game says “Nope! Find something else.”

In Kona, there is a nailed fence and the player probably has a hammer. You cannot dismantle the fence with the hammer. You must instead acquire the crowbar to do the job.

These sorts of issues should either be made flexible (allow multiple solutions if possible) or deliberately forced. Yes, it is annoying that a hammer/handaxe/shovel breaks after using it just once. But perhaps that push is what the player needs to find the intended solution.

4: Moon Logic

Where the previous example assumes common sense, this one is just nonsense. You’ve probably seen these in various “Worst Puzzles Ever” videos. Flying in the face of the world-building and the rest of the puzzles, there is one section that can only be solved by throwing everything in your inventory at the problem. And sometimes not even that.

In The Longest Journey, April Ryan is threatened with petrification by the evil alchemist Roper Klacks. How does she win out? By… doing arithmetic on a calculator. Which he then steals. And is sucked into a pocket dimension for some reason? Nothing about the calculator or Klacks indicates that there would be a connection there.

In the proper setting and precedent, these solutions can work and be funny. But only if they are properly signposted.

Speaking of signposting though…

5: Misleading Signposting and False Hints

Signposting done well can do a lot to avoid DPD. An environmental hint here, an overheard conversation there, and smart set design can guide players through your experience smoothly and make them feel smart.

But you have to be careful. If your player is looking for solutions, everything is a potential hint or solution. And a wrong word in a wrong place can lead to a frustrating wild goose-chase.

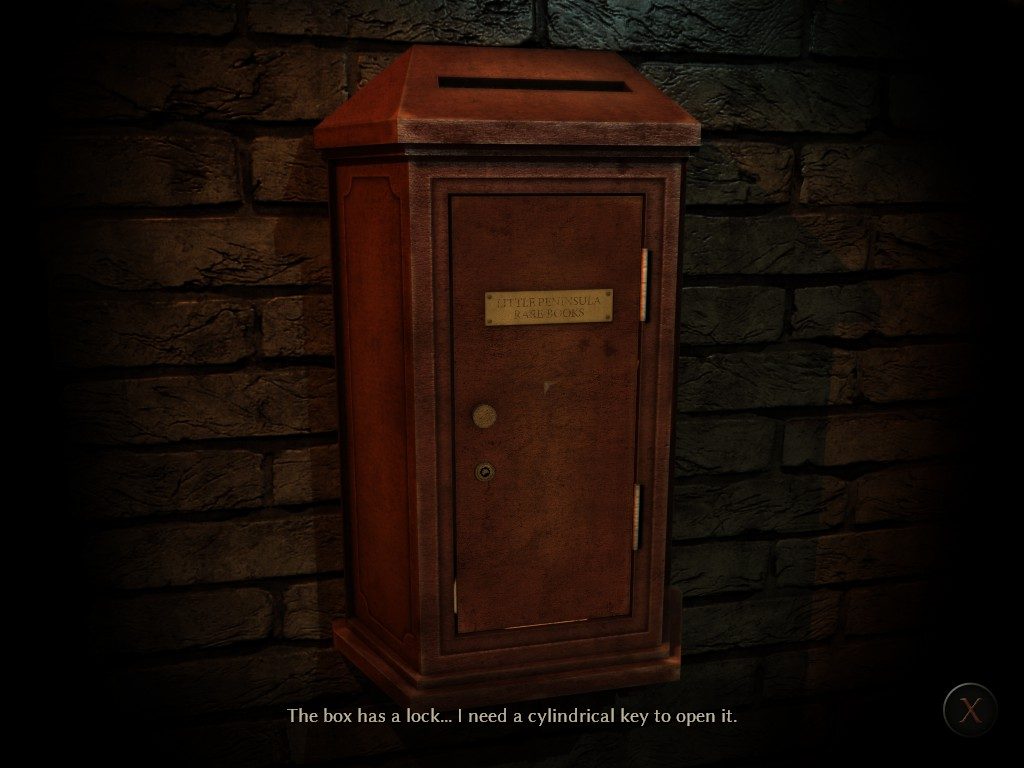

Take Face Noir by Mad Orange. In it, PI Jack Del Nero decides that he needs to open a postbox. If you interact with the box, he ponders “The box has a lock. I need a cylindrical key to open it.” Unfortunately, there is no key (in the game at least). The solution is to use his detective licence to jimmy the lock. But because of the character’s description of the problem, I would not be surprised if many players besides myself spent an annoying chunk of time looking for a key.

This one can only be solved with blind playtests and careful consideration. Really think about what you are telling the player. Will it lead them astray? And if it does, is there something there to steer them back?

6: No Feedback and Unseen Changes

Don’t be silent. For every action, there needs to be a reaction.

Adventure games occasionally have a little something that you can wiggle. The switch doesn’t actually do anything but it’s satisfying to flip, right? Little did they know they were manipulating a silent puzzle.

In the adventure game Schizm, there are three hydraulic valve control wheels. One of them makes it obvious that it’s working. Turn it to the open position and you can hear water flowing. The difference between on and off is clear.

The other two wheels just spin and don’t look or sound like they do anything. Maybe the pipes are broken somewhere? It’s just set dressing, right? No, both wheels are working. The player just can’t tell if they’re doing anything until they turn a corner and press a button.

Alternatively, some games have invisible connections between disparate actions. In Shivers, the player is locked off from even interacting with some of the game’s hotspots until they read a riddle and they can’t open an electrical panel to finish the riddle until they have collected 90% of the game’s macguffins. These ‘invisible walls’ are not foreshadowed in any way and the hotspots do not indicate a change.

7: Needle in a Haystack

This problem is mostly in older adventure games but might pop up in especially detailed modern games. A puzzle would be so easy if only you knew that you could pick up that oil can.

Pixel hunting is the bane of old graphic adventure games. It’s the delicate balance: you want to make everything fit into the world and/or the background but the player also REALLY NEEDS to grab that remote control. When games like Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis came out with full, lovingly rendered screens, there wasn’t disk space to describe every detail. And when games started prerendering their backgrounds and objects, anything was possibly a hotspot.

This falls again into rules and expectations. And the easiest way to explain these is to, well, explain them. Many modern adventure games have a UI shortcut to display hotspot labels over everything you can interact with. This is a huge quality of life improvement and is usually enough to help a player find everything they need.

Action games like The Arkham series, The Witcher series , and the Assassin’s Creed series (among others) have various “vision” modes to highlight enemies, collectables, and interactable gubbins. The genres are different but the goal is the same; make a game that looks amazing while still letting the player know what pieces they can play with.

Next Page: Solutions